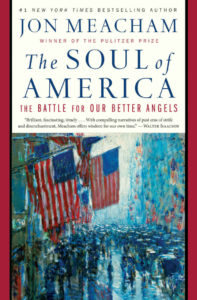

Written partially in response to the 2017 white nationalist rallies in Charlottesville, this 416-page book examines a number of critical turning points in American history:

Written partially in response to the 2017 white nationalist rallies in Charlottesville, this 416-page book examines a number of critical turning points in American history:

- The Civil War, Reconstruction, and the birth of the Lost Cause

- The backlash against immigrants in the First World War and the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s

- The fight for women’s rights

- The demagoguery of Huey Long and Father Coughlin and the isolationist work of America First in the years before World War II

- The anti-Communist witch-hunts led by Senator Joseph McCarthy

- Lyndon Johnson’s crusade against Jim Crow

In each of these crises, author Jon Meacham contrasts the difference between reactionary fear holding us back and hope for a better future leading us to make positive change:

“Fear is about limits; hope is about growth. … Fear points at others, assigning blame; hope points ahead, working for a common good. Fear pushes away; hope pulls others closer. Fear divides; hope unifies.”—p16

I believe the thesis is in line with 2 Timothy 1:7: “For God hath not given us the spirit of fear; but of power, and of love, and of a sound mind.” We must not allow fear to be our motivating factor when making political—or any—choices.

While not an exhaustive history, Meacham emphasizes a number of presidents and other historical figures to illustrate his point:

- Presidents

- Abraham Lincoln

- Ulysses S. Grant

- Theodore Roosevelt

- Woodrow Wilson

- Franklin D. Roosevelt

- Harry S. Truman

- Dwight Eisenhower

- Lyndon B. Johnson

- Other figures

- Martin Luther King, Jr.

- Early suffragettes Alice Paul and Carrie Chapman Catt

- Civil rights pioneers Rosa Parks and John Lewis

- First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt

- Army-McCarthy hearings lawyer Joseph N. Welch

Quotes

On How We Treat Our Fellow Humans

“When the unreconstructed Southerner is the late nineteenth century or the anti-Semite of the twentieth believed—or the nativist of the globalized world believes—others to be less human, then the protocols of politics and the checks and balances of the Madisonian system of governance face formidable tests.”—p17 (emphasis in original)

I’m personally noticing this in the past couple of years: change (and fear of change) can motivate us to dehumanize others, allowing us to blame and punish them for what we fear.

“W.E.B. Du Bois understood what was happening. ‘In 1918, in order to win the war, we had to make Germans into Huns,’ he wrote. ‘In order to win [the Civil War], the South had to make Negroes into thieves, monsters, and idiots. Tomorrow, we must make Latins, South-eastern Europeans, Turks, and other Asiatics into actual “lesser breeds without the law”’—a quotation from Rudyard Kipling’s 1897 imperial poem ‘Recessional.’”—p116–117

Recent rhetoric, particularly against immigration, has this same theme of dehumanizing others not like us. By lumping them all into categories like rapists, murderers, and violent criminals, we justify treating them in ways we wouldn’t dream of treating our neighbors, friends, and loved ones.

On Private vs. Public Sector

“The American ideal of what Henry Clay had called ‘self-made men’ in 1832 is so central to the national mythology that there’s often a missing character in the story Americans like to tell about American prosperity: government, which frequently helped create the conditions for the making of those men.

“Many Americans have never liked acknowledging that the public sector has always been integral to making the private sector successful. We often approve of government’s role when we benefit from it and disapprove when others seem to be getting something we aren’t. Given the American Revolution’s origins as a rebellion against taxation and distant authority, such skepticism is understandable, even if it’s not well-founded. We have long proved ourselves quite capable of living with this contradiction, using Hamiltonian means (centralized decision-making) while speaking in Jeffersonian rhetorical terms (that government is best which governs least).”—p180

Too often we forget how much the free market depends on services provided by government, particularly for infrastructure: roads, utilities, funding for the invention and development of the internet, etc.

On Political Life

“McCarthy, though, was something new in modern political life: a freelance performer who grasped what many ordinary Americans feared and who had direct access to the media of the day. He exploited the privileges of power and prominence without regard to its responsibilities; to him politics was not about the substantive but the sensational. The country feared Communism, and McCarthy knew it, and he fed those fears with years of headlines and hearings. A master of false charges, of conspiracy-tinged rhetoric, and of calculated disrespect for conventional figures (from Truman and Eisenhower to Marshall), McCarthy could distract the public, play the press, and change the subject—all while keeping himself at center stage.”—p185

Sound familiar? Replace McCarthy’s name with Trump, change “Communism” to “immigration”, and remove the specific people mentioned, and it would remain an accurate description.

Summary

This book is a good reminder that fear is restrictive, holding us back from making any real improvement. We must look ahead with hope and work for the common good, not just for what will improve our own situation. It’s also an encouragement that as a nation, we have been through many dark times and ultimately moved past them.