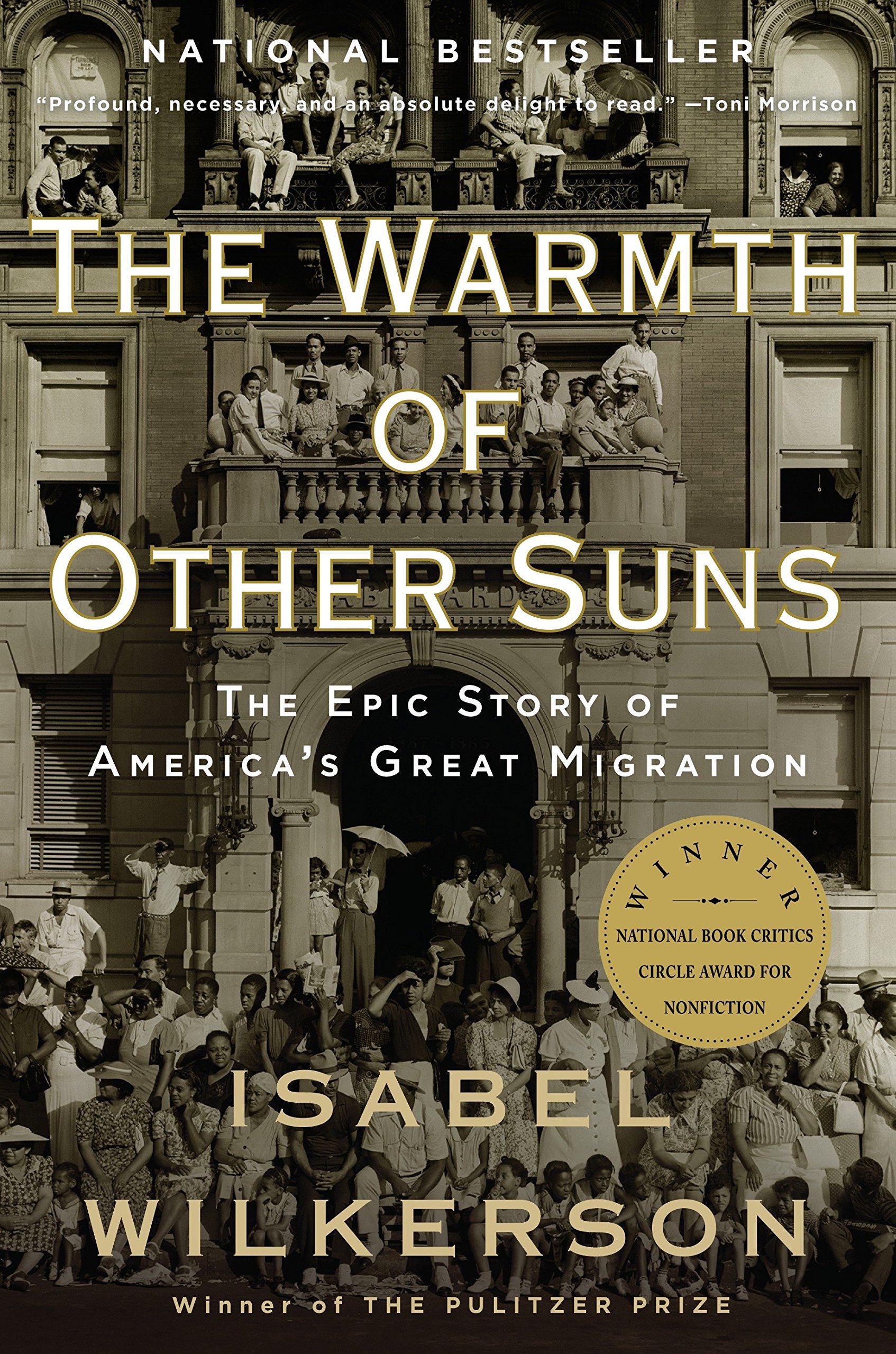

Description

From 1915 to 1970, this exodus of almost six million people changed the face of America. Wilkerson compares this epic migration to the migrations of other peoples in history. She interviewed more than a thousand people, and gained access to new data and official records, to write this definitive and vividly dramatic account of how these American journeys unfolded, altering our cities, our country, and ourselves.

With stunning historical detail, Wilkerson tells this story through the lives of three unique individuals: Ida Mae Gladney, who in 1937 left sharecropping and prejudice in Mississippi for Chicago, where she achieved quiet blue-collar success and, in old age, voted for Barack Obama when he ran for an Illinois Senate seat; sharp and quick-tempered George Starling, who in 1945 fled Florida for Harlem, where he endangered his job fighting for civil rights, saw his family fall, and finally found peace in God; and Robert Foster, who left Louisiana in 1953 to pursue a medical career, the personal physician to Ray Charles as part of a glitteringly successful medical career, which allowed him to purchase a grand home where he often threw exuberant parties.

Wilkerson brilliantly captures their first treacherous and exhausting cross-country trips by car and train and their new lives in colonies that grew into ghettos, as well as how they changed these cities with southern food, faith, and culture and improved them with discipline, drive, and hard work. Both a riveting microcosm and a major assessment, The Warmth of Other Suns is a bold, remarkable, and riveting work, a superb account of an “unrecognized immigration” within our own land. Through the breadth of its narrative, the beauty of the writing, the depth of its research, and the fullness of the people and lives portrayed herein, this book is destined to become a classic.

My Thoughts

I thought this book was excellent. Far from a dry examination of events and causes, it began with some historical context and examples of life under Jim Crow laws in the South.

It picks up the stories of three specific individuals and follows them through life, starting with their decision to leave their homeland in the South and migrate to the North to have the freedom they were promised by their country.

The narrative jumps between the characters, but rather than keeping the chronological timeline strictly coherent, it tracks their life progress. For instance, the chapter describing when they left is set in three different decades.

One thing that really struck me is just how recently Jim Crow laws were enforced, resulting in—for all practical intents and purposes—the continuation of slavery.

Quotes

An invisible hand ruled their lives and the lives of all the colored people in Chickasaw County and the rest of Mississippi and the entire South for that matter. …[T]here was mostly fear and dependence—and hatred of that dependence—on both sides.

— Page 43

Across the South, someone was hanged or burned alive every four days from 1889 to 1929, according to the 1933 book The Tragedy of Lynching, for such alleged crimes as “stealing hogs, horse-stealing, poisoning mules, jumping labor contract, suspected of killing cattle, boastful remarks” or “trying to act like a white person.” Sixty-six were killed after being accused of “insult to a white person.” One was killed for stealing seventy-five cents.

— Page 53, emphasis added

Jim Crow had a way of turning everyone against one another, not just white against black or landed against lowly, but poor against poorer and black against black for an extra scrap of privilege.

— Page 63

The dance of the compliant sharecropper conceding to the big planter year in and year out made it seem as if the ritual actually made sense, that the sharecropper, having been given no choice, actually saw the tilted scales as fair. The sharecropper’s forced silence was part of the collusion that fed the mythology.

— Page 198

The South, totalitarian and unyielding, was at that very moment succeeding at what white Harlem leaders were so desperately trying to do, that is, controlling the movements of blacks by controlling the minds of whites.

— Page 288

Contrary to modern-day assumptions, for much of the history of the United States—from the Draft Riots of the 1860s to the violence over desegregation a century later—riots were often carried out by disaffected whites against groups perceived as threats to their survival. Thus riots would become to the North what lynchings were to the South, each a display of uncontained rage by put-upon people directed toward the scapegoats of their condition. Nearly every big northern city experienced one or more during the twentieth century.

— Page 314

The reality was that Jim Crow filtered through the economy, north and south, and pressed down on poor and working-class people of all races. The southern caste system that held down the wages of colored people also undercut the earning power of the whites around them, who could not command higher pay as long [as there were colored people willing to do the same jobs].

— Page 363

[T]he sociologist Gunnar Myrdal called [this] the Northern Paradox: In the North, Myrdal wrote, “almost everybody is against discrimination in general, but, at the same time, almost everybody practices discrimination in his own personal affairs”—that is, by not allowing blacks into unions or clubhouses, certain jobs, and white neighborhoods, indeed, avoiding social interaction overall. “It is the culmination of all these personal discriminations,” he continued, “which creates the color bar in the North, and, for the Negro, causes unusually severe unemployment, crowded housing conditions, crime and vice. About this social process, the ordinary white Northerner keeps sublimely ignorant and unconcerned.”

— Page 441

The hierarchy in the North “called for blacks to remain in their station,” Lieberson wrote, while immigrants were rewarded for “their ability to leave their old world traits” and become American as quickly as possible.

— Page 475

With the benefit of hindsight, the century between Reconstruction and the end of the Great Migration perhaps may be seen as a necessary stage of upheaval. It was a transition from an era when one race owned another; to an era when the dominant class gave up ownership but kept control over the people it once had owned, at all costs, using violence even; to the eventual acceptance of the servant caste into the mainstream.

— Page 608

Perhaps it is not a question of whether the migrants brought good or ill to the cities they fled to or were pushed or pulled to their destinations, but a question of how they summoned the courage to leave in the first place or how they found the will to press beyond the forces against them and the faith in a country that had rejected them for so long. By their actions, they did not dream the American Dream, they willed it into being by a definition of their own choosing. They did not ask to be accepted but declared themselves the Americans that perhaps few others recognized but that they had always been deep within their hearts.

— Page 608

View on Bookshop

Note: this is an affiliate link, so I may get a small commission if you purchase using the link. This commission does not affect the content of this post.